"Prisoners are not permitted to:

a) possess sharp and pointed metal objects and items;

b) possess cards and games of chance;

c) possess any documents except receipts for items and valuables that have been confiscated;

d) sing, make noise, or remain in prohibited areas;

e) go into other rooms;

f) have alcoholic beverages;

g) exchange letters or receive visitors."

Provisional order of the NKVD, July 1945.

(Sergej Mironenko u. a.: Die Sowjetischen Speziallager in Deutschland, Bd. 2, Berlin 1998)

Prisoners were prohibited from most activities. Contact with other barracks was forbidden and punished. Because of the strict contact prohibitions, the special camps are sometimes called “silent camps.”

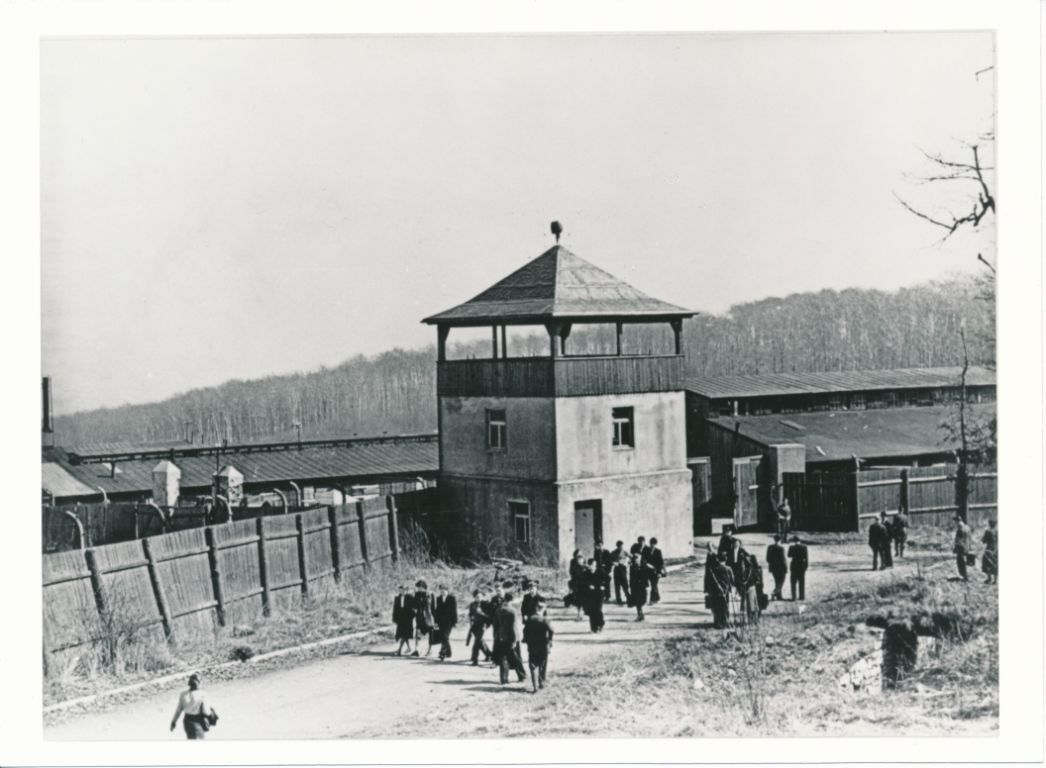

Watchtower No 1 (Easttower) with the wooden fence, 1952. ©Buchenwald Memorial

The photo was taken after the special camp was dissolved. On the left is the wooden fence erected in 1947.

It was extremely rare to successfully smuggle messages out of the camp. Günter Schallenberg embroidered this message onto a piece of fabric in 1947 and threw it out of the train during transport from Jamlitz to Buchenwald. A railway employee found the message and sent it to his family. Günther Schallenberg was released from the Buchenwald special camp in 1948. In 1995, he handed the document over to the Buchenwald Memorial.

"The plan was finalized: loopholes had to be cut into the three fences. Recognized prerequisites: crawl as flat as possible on the ground, cut only unpowered wires from the fences, avoid any contact with electricity, no rain or snow, but very thick fog, which greatly reduced the luminosity of the many lamps. [...] The most important escape tool was a pair of tin snips, which we used to cut openings in the three fences and the wire entanglements so we could slip through."

Recollections of Joachim Kretzschmar, 1998.

(Joachim Kretzschmar: Fünf kamen durch, Altenburg 1998)

In his report, Joachim Kretzschmar describes the difficult preparations for his escape from Special Camp No. 2. Together with four others, he fled to the US occupation zone in December 1946.