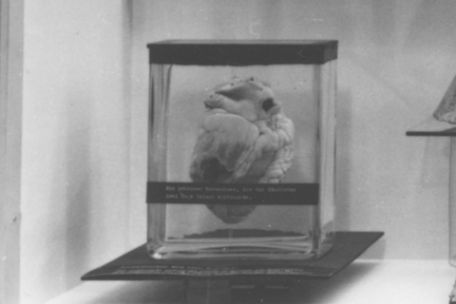

All human remains are now stored in the new underground storage facility built in 2013 for the collection, art collection and archive. There they are housed in their own climate-controlled area, the conditions of which are constantly monitored.

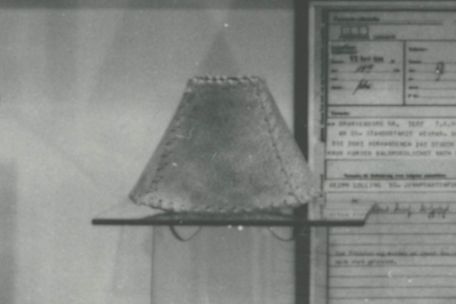

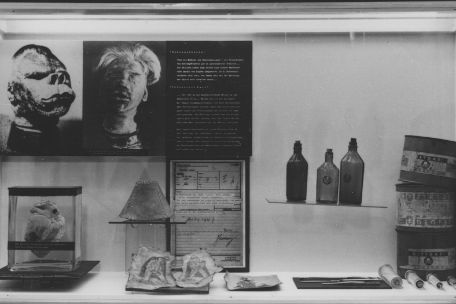

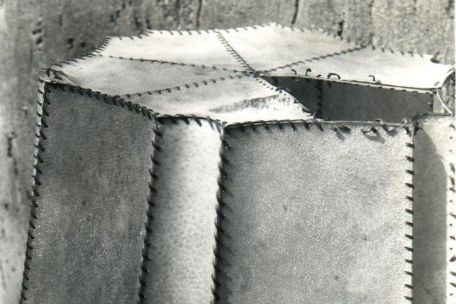

In recent years, we have endeavoured to reconstruct the provenance of the "human remains" in the collection as far as possible. There are a total of twelve objects in the collection with such a connection. Other human remains from Buchenwald are now in the collection of the German Historical Museum in Berlin and the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Maryland.

Not least because these crimes in Buchenwald and the authenticity of the surviving human remains are repeatedly called into question in historical revisionist circles, the Buchenwald Memorial has decided to commission new forensic expertises.

Forensic biologist Dr Mark Benecke, a publicly appointed and sworn expert for the securing, examination and evaluation of biological evidence since 2001, was commissioned to carry out the scientific investigations. Several laboratories with the best possible laboratory techniques were involved. This dossier provides an overview of their findings.