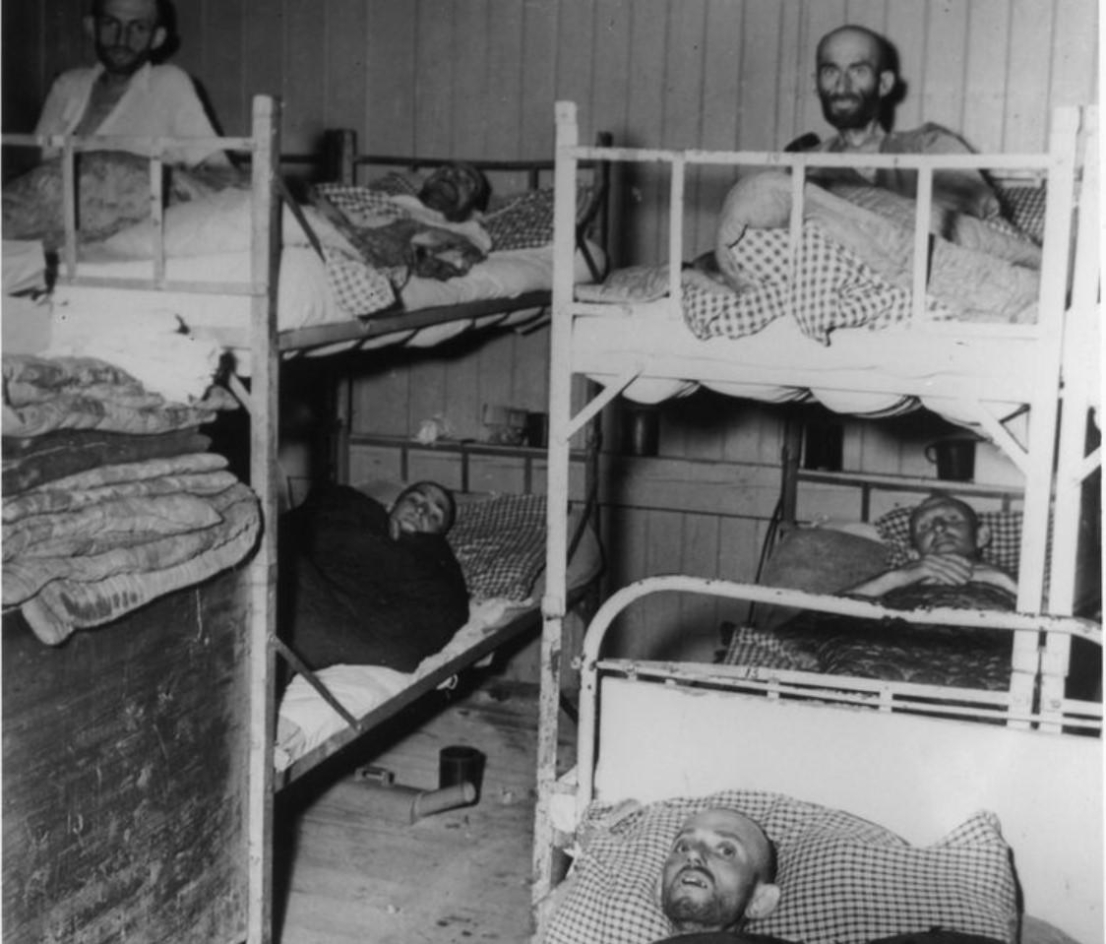

©Bettmann/Corbis

Rabbi Herschel Schacter, US-Army chaplain, Report 1981 (Extract)

From floor to ceiling were hundreds upon hundreds of men and very few boys who were strewn over scraggly straw sacks looking down at me, looking down at me out of dazed eyes. [...] I remember their eyes, looking down, looking out of big, big eyes - that's all I saw were eyes - haunted, crippled, paralyzed with fear. They were emaciated skin and bones, half-crazed, more dead than alive.

And there I stood and shouted in Yiddish "Sholem Aleychem, Yiden, yir zent frey!" "You are free." The more brave among them slowly began to approach me [...], to touch my Army uniform, to examine the Jewish chaplain's insignia, incredulously asking me again and again, "Is this true? Is it over?"

Dr. Philip Lief, US Army captain, report of 1981 (excerpt)

There were many sick inmates, and their death rate per day was approximately 145. We had a great deal of plasma with us and we would give the inmates who were terminatelly ill infusions of plasma. Some of the inmates couldn't wait and they opened the bottles of plasma and started to drink the plasma, although we told them that this had to be given intravenously. At autopsy many of the patients showed manifestations of marked, advanced pulmonary tuberculosis, with large cavitation in both lungs.

[...] Many of the inmates were shipped back to other centers for refugees and we took care of the non-transportable and terminally ill patients or inmates. The first thing we had to do was to pick out the most severely ill patients or inmates, those who were terminally ill, and to try heroic measures such as transfusions, intravenous feeding and therapy... and supportive therapy in order to try to help these people to survive. Those inmates who had malnutrition were given high calorie diets and were sent for psychiatric care in many cases. [...]

We tried to keep the people from going into shock. We tried to build up their resistance as much as possible. So it was supportive care primarily that we were concerned with. We had penicillin with us so we tried to use that and whatever therapy was available at that time, in 1945. We didn't have enough blood at that time but we had enough plasma. We had enough medication. Unfortunately, most of the people there had really far advanced disease and many of them could not be saved because of that.

Report of the 120th Evacuation Hospital, June 10, 1945 (excerpt)

"At the time this unit took over the camp there were an estimated 21,000 prisoners there. The greatest problem facing the unit was one of sanitation. The water supply had been cut off due to the destruction of one of the mains by explosives. Latrine facilities in the camp were virtually non-existent and hygiene of any kind was apparently unknown. Prisoners' barracks were in the worst possible condition. Lighting was inadequate, barracks were filthy, barracks overcrowded, inmates underfed and underclothed. Upon taking over the camp, the unit began delousing and cleaning buildings which had formerly housed SS guards. As these buildings were cleared, the worst cases were transferred."

Report of the 120th Evacuation Hospital, 10 June 1945 (excerpt)

"Of those patients admitted and those examined the most prevalent causes of sickness were dysentery, malnutrition and tuberculosis. Typhus and pneumonia were also quite common. During the first few days officers and enlisted man moved out of tents and were billeted in buildings. A mess was set up in the Buchenwald camp to help feed the inmates. Food consisted of soft and liquid diet (i. e. soup, milk, oatmeal, and meat stew).

One of the surest signs that the unit's work was effective was the fact that within three (3) days after our taking over the camp, the death rate dropped from one hundred (100) per day to less than thirty (30)."

Report of the 120th Evacuation Hospital, June 10, 1945 (excerpt)

"On 19 April 1945 the camp was visited by a body of 10 British Members of Parliament to see at first hand the conditions at the camp. They were conducted through the camp and wards and were very favorably impressed by the work being done by this unit. On their inspection they were shown prisoner barracks, children's quarters, the camp crematorium, the notorious 'Block 61' and the SS barracks which had been taken over for use as wards. They spoke with some of the patients, through interpreters and found the patients to be grateful for the care being taken of them by the Americans.

The following day, 20 April 1945, a group of twelve (12) U S congressmen visited the camp to make a survey of conditions. They likewise were horrified at living conditions and the treatment of the inmates by the Germans and were greatly impressed with the progress made by this unit in correcting these conditions.

On 21 April 1945, we were honored by a visit by US Senators sent to investigate the Buchenwald Concentration Camp."

Report of the 120th Evacuation Hospital, June 10, 1945 (excerpt)

We were relieved from duty on 23 April 1945 but by this time food had been procured and transported to the camp to provide the patients with a ration comparable to an "A" ration. Since Buchenwald Concentration Camp was our first chance to function since arriving on the continent, both the officers and enlisted men worked hard to prove their capabilities. Each person felt that he was accomplishing something and in addition to efficient and cooperative work from all sections, morale was raised to a higher degree.

Movement to our next area, Kersbach, Germany, was started at 6:00 am April 25, 1945 and completed 6:00 pm April 28, 1945 with the return to duty from TDY of the unit's nurses.

Time magazine, May 14, 1945

“Back from the grave” is the name of the Time magazine article dated May 14, 1945. The reporter Percy Knaut reports as an eyewitness of the efforts of the 120th U.S. Army Evacuation Hospital to keep the sick and completely exhausted Buchenwald prisoners alive.