Before the end of the war, the Soviet secret police set up special camps in the eastern territories of the German Reich. These camps were disbanded by February 1946, and their prisoners were distributed to the special camps in the Soviet occupation zone.

A total of ten camps were set up in the Soviet occupation zone. They were located in existing buildings from the Nazi era, such as barracks, prisons or former concentration and prisoner of war camps. The Soviet occupying power dissolved most of the special camps by 1948. Only Special Camp No. 1 in Oranienburg, No. 2 in Buchenwald and No. 3 in Bautzen remained in existence until 1950.

Some of these camps were eventually closed, repurposed or merged with other camps. For example, Special Camp No. 7 Weesow was incorporated into Special Camp No. 7 Sachsenhausen in summer 1945.

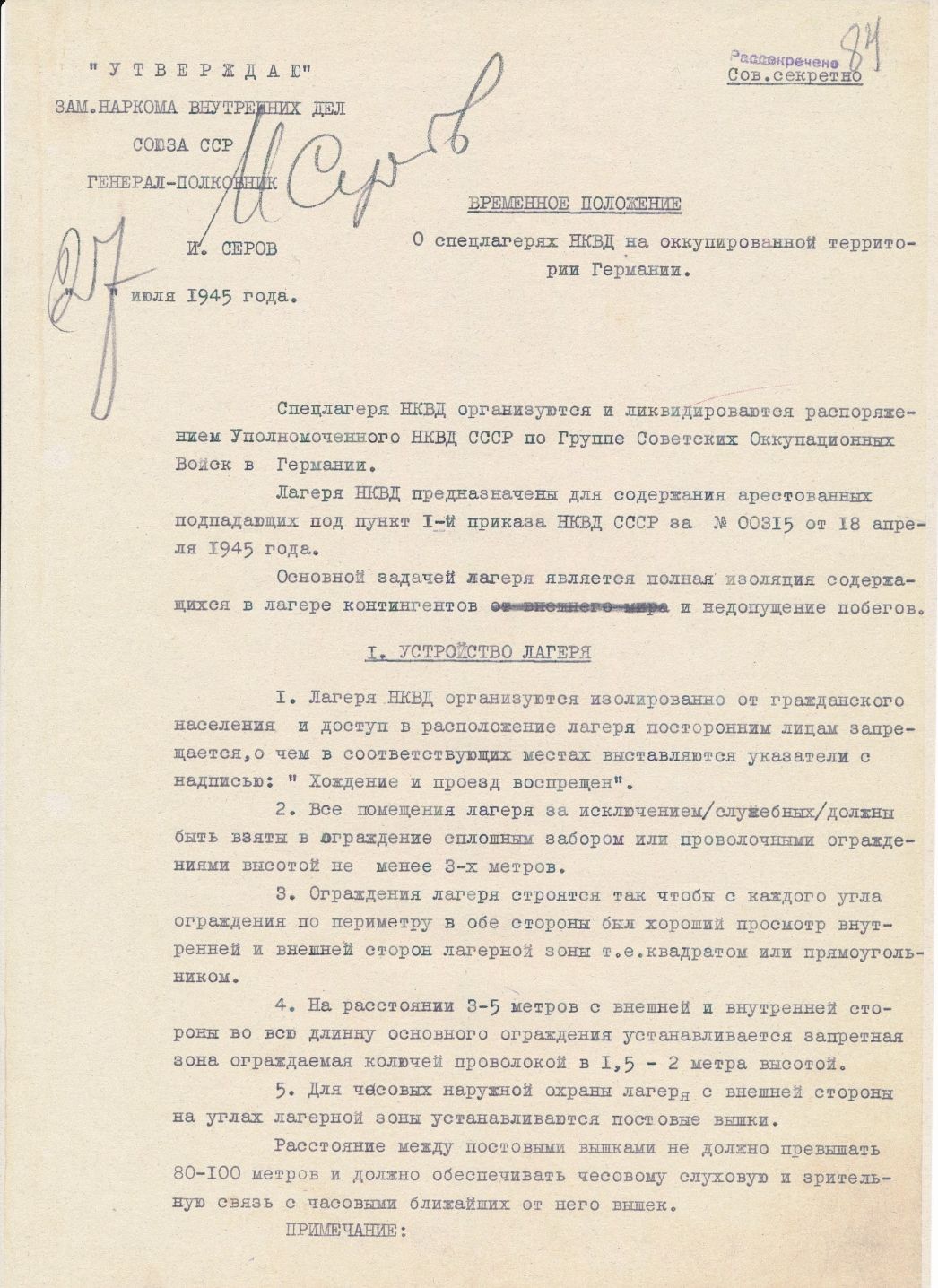

This order regulated the operation and surveillance of the Special camps.

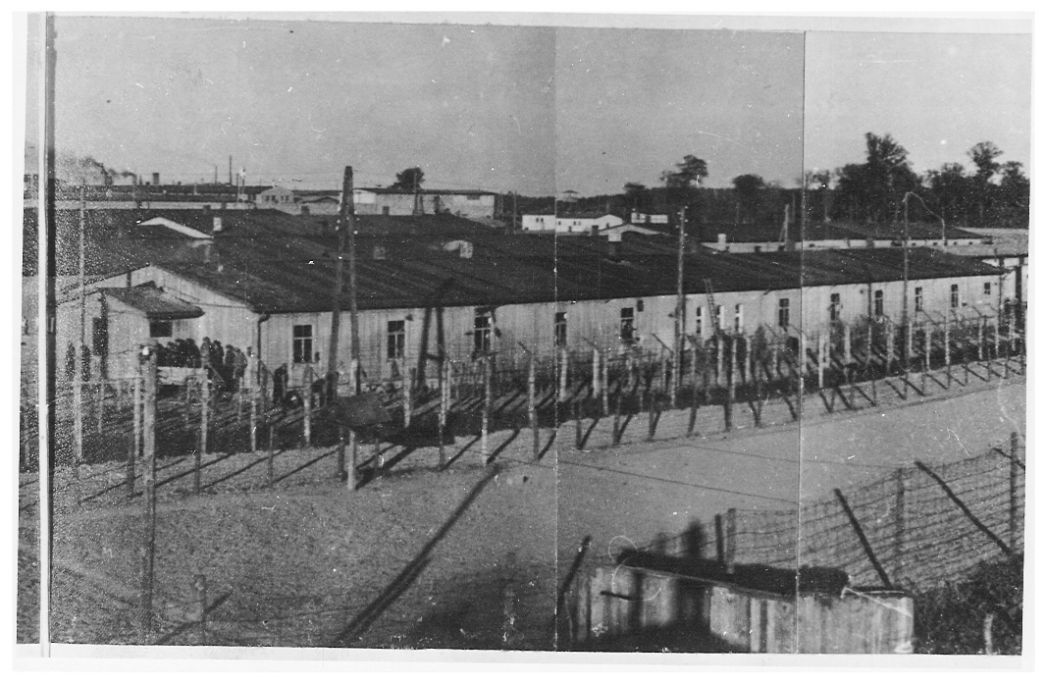

Barracks in the Special Camp Funfeichen, between 1945 and 1948. ©Stadtarchiv Neubrandenburg

The photo was taken from a watchtower by an employee of the Soviet camp administration.

“On October 12, I was then taken by the German police without any explanation.” Video interview with Joachim Kretzschmar about the circumstances of his arrest in Altenburg, October 28, 1996.

Arrests took place mostly at night, but also during the day. The Soviet secret service authorities worked together with the German police. The detainees were rarely given an explanation for their arrest.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

Transcript:

"On October 12, I was picked up by the German police. They asked me to come to the police station without giving me a reason, but I was told to take some warm clothes with me. So that was already a sign that it probably would be more than just two days. And around this time, of course, there was already talk everywhere that people had been arrested, locked up, hadn't come back and so on. Yes, and then came this arrest; I was sent to [the] district court in Altenburg, which was occupied by the Russians at the time. And I think I was there from October 12, yes, until November 2 or 3, (and I was only) interrogated once.[Interviewer's question: Only once?], Yes, I was interrogated once. I mean, you can't really say interrogated; I was talking to a Russian major and he was just saying: “Yes, yes...” - So I had been – well, how do I put it? – passing on the Führer's word; I’d been collecting old material, arranging for others to do so and collecting for the winter farms, and all these things would have prolonged the war. But, um, there was no further interrogation, no penalty, no verdict or any kind of trial whatsoever. Nothing at all. I was in a cell with two other older prisoners. To describe the cell, uh… it’s of course unfathomable today, the conditions under which prisons were run back then. Sanitary facilities were almost a taboo. And… uh... both of them were released in the course of these 10-12 days, during the time I was in prison. In the end, I was alone. One night, the cell was torn open; there was a big commotion in the corridors outside. Probably, everyone who was still there had to leave. Then we were led into the yard, and from there out to the street, where there was a normal bus. We were loaded onto the bus, and then the journey started. I just kept hoping that we were going west and not east. After passing the towns of Schmölln and then Ronneburg on the way to the highway, I thought: well, as long as we’re going to Ronneburg and Gera, we must be going west. [I thought] the destination was probably Weimar, because we knew that something was going on in Buchenwald. But we didn't know that the Russians had, let's say, “re-established” the camp; that the camp was functional again to begin with."

“I also gave names on the third night.” Video interview with Joachim Tasler about his interrogation experiences and the background to his arrest, Lemgo 25.09.1996.

During the interrogations, the Soviet secret service was primarily interested in names of relatives who and information on the function and structure of all organizations that posed a security risk to the occupying power.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

Transcript:

"I was born in Dresden on November 13, 1930, spent my youth on the Weißer Hirsch in Dresden, attended elementary school and then went to grammar school in Dresden – until the bombing on the night of April 13, 1945. I witnessed this attack from the outskirts [of Dresden]. After that, I had no opportunity to continue my education and then, as a 14-year-old, I started a commercial apprenticeship in a grocery store on June 1, 1945. On Tuesday, July 10, 1945, I was taken from there to the police station for questioning by the police in the Dresden Weißer Hirsch district, and in the evening I was taken to the district mayor's office. I had to wait in the mayor's anteroom until I was called in to talk to the people there: First Lieutenant of the GPU, an interpreter, a sergeant armed with a machine gun. They told me that I was to come with them to Dresden for questioning. And so began my journey into detention."

“The interrogations were only ever carried out at night.” Video interview with Joachim Tasler about his arrest and interrogation experiences, Lemgo, September 25, 1996.

Some prisoners were only interrogated once. Others had to undergo countless nights of interrogation, often accompanied by violence. The interrogations were conducted by NKVD interrogation officers accompanied by guards. In most cases, an interpreter was present. The interrogations were recorded in Russian, then presented to the interrogated persons for signature. These signed interrogation protocols were considered an admission of guilt by the Soviet secret service.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

Transcript:

"I was taken from there by streetcar to the Wehrmacht detention center in Dresden, near the former barracks of the German Wehrmacht, and then remained there from the evening of July 10 until the morning of Sunday, July 15, 1945. As was customary, the interrogations were only ever carried out at night, from 10 o'clock in the morning until 4-5 o'clock in the morning. (I) was interrogated intensively during the following two nights. Sometimes they beat me on my chest and back to spur me on. I told myself: “You're not signing anything!” but after two or three nights, when one thing or another hurt – and because, as a 14-year-old, I simply didn't have the strength to resist – I of course ended up signing eight or ten A4 pages, written in Russian. They read out to me that I had been arrested on suspicion of espionage and being a “werewolf.” I was told that I had taken part in one or two ... um ... yes ... things, in one or two things where posters and slogans were painted, which wasn't true. But I was more or less blamed for that, and on Sunday morning the cell buildings were emptied and a transport of 15 people - we had about seven guards - was taken on a truck to Bautzen [Prison], the ‘gelbe Eend’ [lit. ‘Yellow Misery’].”