Transcript

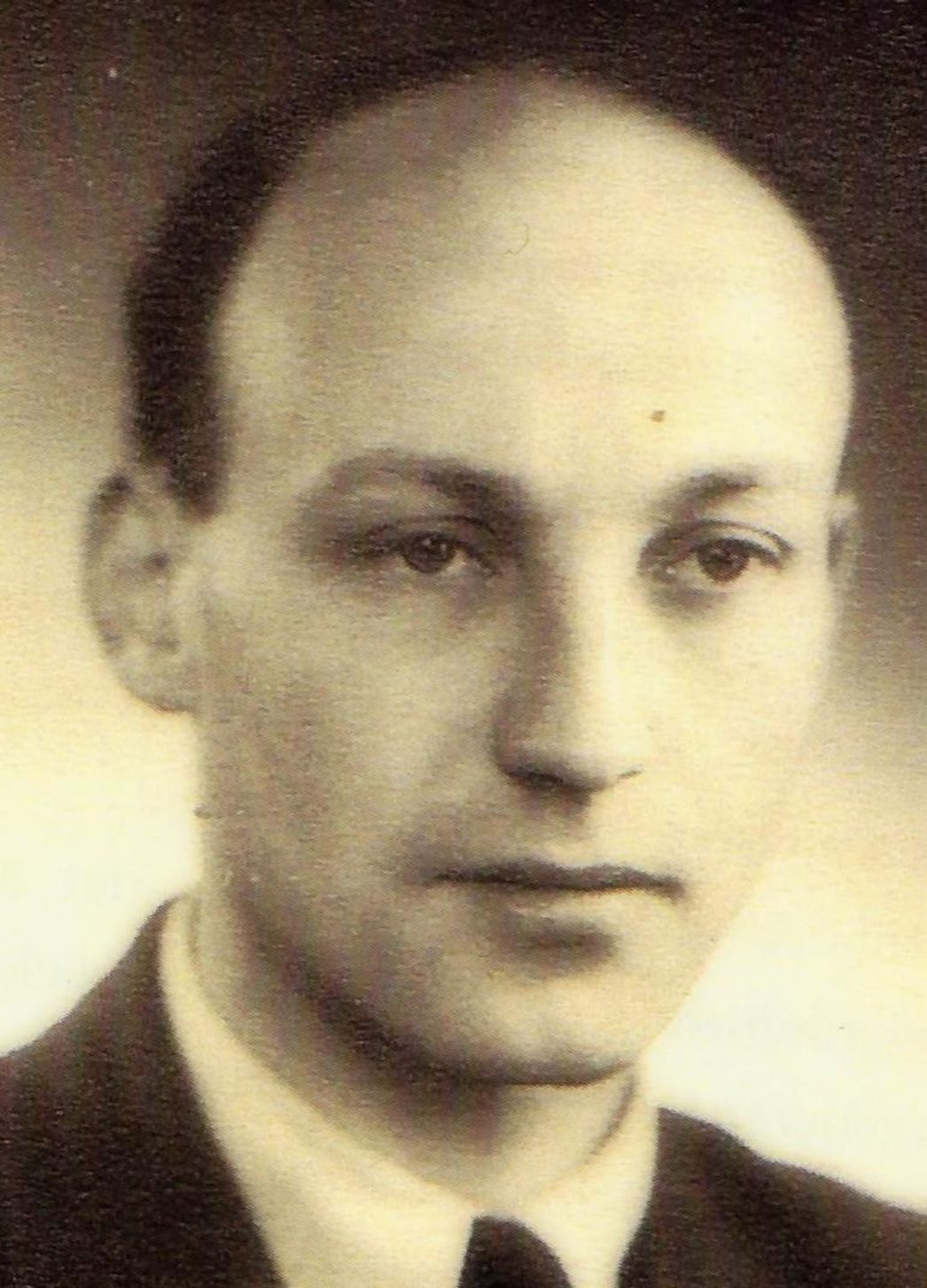

Narrator On the 17th of August 1944, shortly before Paris was liberated, a train left Paris for Germany. It included a cattle wagon labelled “Jewish Terrorists.” In it were 50 Résistance fighters who were being removed from the Drancy camp near Paris – among them Max Windmüller. The commander Alois Brunner was taking them as hostages while clearing out of France. Some of the French prisoners managed to escape even before the train gathered speed. But Max Windmüller was not able to. On the 25th of August 1944, he was registered in the Buchenwald concentration camp as a “Jewish political inmate”.

Shortly before the transport left, he had an opportunity to write to a friend:

Max Windmüller “When I was at the Gestapo headquarters, my hands tied behind my back, on my knees for 24 hours, I thought about many things. [...] I also thought of all the comrades who are now in Spain. If we had not done what we did, there would have been even more victims and more comrades would have been deported to Poland. I believe this fact alone already gives us satisfaction.”

Narrator What exactly did Windmüller do? Why did the Nazis consider him a “Jewish terrorist”?

Let’s go back in time a bit: The Windmüller family from the town of Emden in East Friesland fled to the Netherlands as early as March 1933. There, one of Max’s brothers led a group of youths who trained in agriculture to prepare themselves for immigration to Palestine. Max was one of them. In 1939 he had already boarded a ship when his friends talked him into staying and joining the resistance.

Max Windmüller joined the resistance group of Joop Westerweel, organizing means of escape primarily for Jewish children and youth. He was arrested, escaped and was given forged documents. From then on he went by the name Cornelius Andringa, while his friends called him Cor. Together, they saved more than 400 lives, smuggling Jewish people through France, across the Pyrenees and on to Spain. In July 1944, a double agent betrayed the group to the Gestapo.

Only days before his second arrest, Max Windmüller wrote in a letter to his Brother:

Max Windmüller “If in the end, I fail and [...] fall, I will know that my efforts were not in vain and that the pains of fighting were worth it for the people, who deserved it. Even if I should be subjected to the hardest torture, I will not buckle, I will not bow my head to the scum of humanity. I have the will and I am duty-bound to fight to the end.”

Narrator One day before the liberation of Buchenwald, the SS abducted Max Windmüller, a friend of his, and nearly 4500 further inmates, taking them in open wagons to Flossenbürg. From there they went on a death march toward Dachau. Max fell seriously ill. His friend Paul Wolf remembered:

Paul Wolf “Cor had become terribly emaciated [...]. Between Winklarn and Rötz near Cham, Cor could go no further, no matter how much he thought of the effort, of France and of the chaverim. His throat had seized up, he no longer spoke and was tired. He staked everything on one chance, just so he could rest for a moment. But the SS did not let that happen. They shot right away.”

Narrator The next day, the inmates came across American troops and were freed.