Transcript

Narrator Heinrich Himmler was out for revenge. Two weeks after the failed assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler, the head of the SS made himself clear in a speech delivered to Gauleiters: an “absolute detention of kinship inmates” was going to be introduced, and the Stauffenberg family, the second most powerful man in the Reich thundered on, was to be “extinguished down to the last member”.

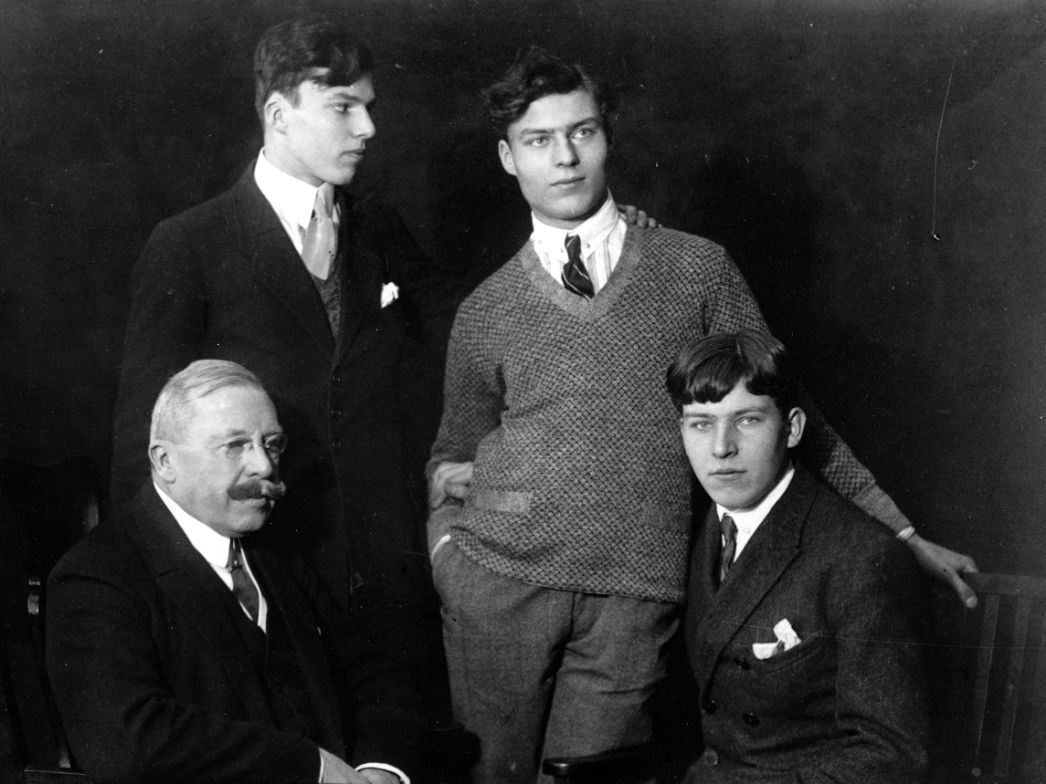

Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg was one of the central figures of military opposition to the Nazis: On the 20th of July 1944, he placed an explosive charge in the Führer headquarters, which was to kill Hitler but instead only injured him slightly. The planned coup failed and the regime struck back mercilessly. Stauffenberg and several co-conspirators were shot the very next day; others who were presumed to have participated or to have had knowledge of the attempt were pursued, incarcerated, interrogated, tortured, sentenced in show trials by the so-called People’s Court and executed.

From the beginning it was obvious that the Nazi leaders had their sights set not only on the resistance fighters themselves, but on their families as well, completely regardless of whether the relatives knew about the resistance activities or not. This was especially true in the case of the Stauffenberg family: Their possessions were confiscated. By late July, 1944, some family members were already interned and the children of the Stauffenberg brothers had been brought to a home in Bad Sachsa.

“Sippenhaft” or “kinship liability” that was threatened by Himmler was illegal even in the “Third Reich”. It was a terror measure against political opponents that was only used deliberately and in individual cases, for example as a means of oppression against the families of deserters. It was only after the failed assassination attempt that the regime began detaining kinship inmates in large numbers. In July and August of 1944 alone, the Gestapo took more than 140 people from more than 30 families into custody; men, women, elderly, youth and children arrived – often separated from each other – in prisons, seized hotels and also in concentration camps, where, however, the “kinship inmates” were given special accommodation and preferential treatment.

Beginning in February 1945, the Gestapo transferred numerous “kinship inmates” from other places of detention to Buchenwald. They were housed away from the inmate camp in the so-called isolation barrack which, after having been destroyed in the bomb attack of August 1944, had now been rebuilt. Soon, more than 50 people would be interned there. One of them was Alexander Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg, a professor of ancient history and the older brother of the assassin; late in July, he had been arrested in Greece while serving in his military unit. Along with him, other Stauffenbergs were detained: one of his sisters-in-law, a cousin and some of their children.

Their hopes of being liberated by the Americans were dashed when they learned that “kinship inmates”, just like the prominent special inmates interned in Buchenwald, were considered Himmler’s hostages. Early in April 1945, the SS ordered that both groups be evacuated. The journey into the unknown via Regensburg, the Dachau concentration camp and Innsbruck only ended on the 4th of May 1945 in South Tyrol, where US troops freed the hostages from German hands.