Structure of the exhibition

In the liberated camp

After the liberation of the camp, survivors tried to make the reality of Buchenwald imaginable by depicting the camp as it had been before the liberation. Alongside journalistic accounts of the conditions in the Buchenwald concentration camp, survivor memoirs were published. The "Report of the International Camp Committee" held a special place among them. This section of the exhibition shows, for instance, how leading members of the camp Communist Party (KPD) began to organize the remembrance of the Buchenwald concentration camp.

From the memorial in Weimar to the grove of honor on the Ettersberg

Initial plans and efforts to honor the dead took place in Weimar. Among them, two different monument concepts from 1946 were drawn up by the former prisoner Werner A. Beckert and prominent communist survivors. Ernst Thape, former Social Democratic prisoner who was then the Minister of Culture of Saxony-Anhalt, proposed in 1947 that a large "Monument to the Unknown Victims of Fascism" be erected on the Ettersberg.

From the Buchenwald Committee Memorial to the National Monument of the GDR

In 1947, under the direction of the "Victims of Fascism" department of the Weimar city administration and the municipal construction office, a grove of honor was added to the Ettersberg cemetery below the Bismarck Tower. In 1950, the Politburo decided to preserve only some relics of the former concentration camp, including the gate building and the crematorium.

On December 14, 1951, the VVN announced two restricted competitions to design the grove of honor and to turn the crematorium courtyard "into a commemorative site to Ernst Thälmann."

At the end of 1953, the Politburo reorganized the responsibilities for the construction of the memorial. The Ministry of Culture was now responsible for the construction of the memorial grove and monument

The SED party leadership, comprising of Moscow emigrants, for one, envisioned a remembrance evoking the superiority of communism by the example of Buchenwald, yet on the other hand rejected the idea of legitimizing the political claims of the surviving Buchenwald communists.

Within the party, new investigations were conducted against them for their behavior as political functionaries. Gradually, the SED leadership ousted all former leading members of the camp Communist Party. As early as 1950, Ernst Busse and Erich Reschke were arrested by Soviet authorities, sentenced and transferred to the Workuta camp in Siberia. The SED leadership planned a trial against Walter Bartel modeled after the Slansky trial in Prague.

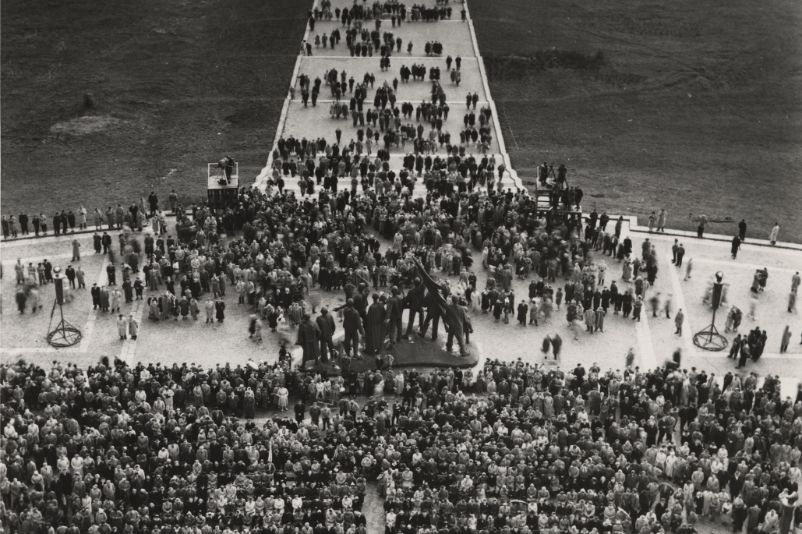

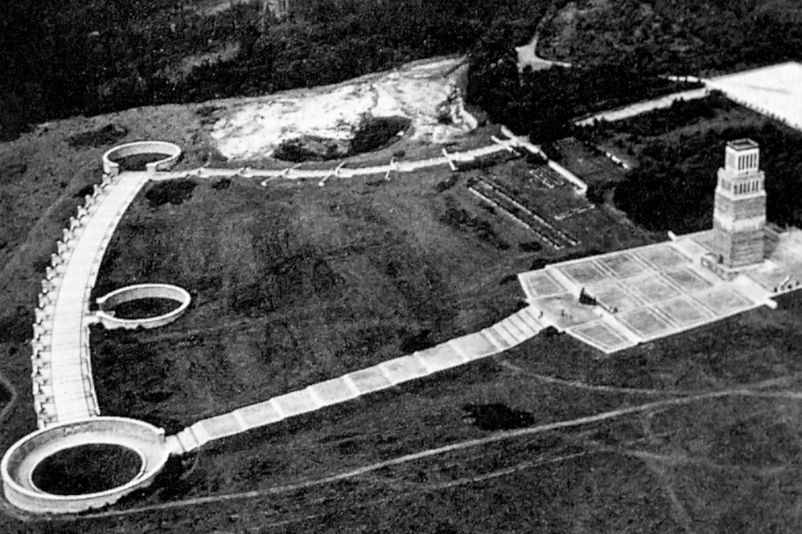

The Buchenwald National Monument and Memorial was inaugurated on September 14, 1958. The design of the former concentration camp grounds and the monument was based on the central theme of "victory through death and struggle".

Scheduled tours of the memorial began at the crematorium, led through the preserved sections of the former camp grounds and the "Museum of Resistance," and ended at the monument at the "Tower of Freedom." The descent into the "Night of Fascism" was followed by the ascent into the "Light of Freedom". The walled rings mark mass graves found after the liberation.

Designed as a secular path of purification, the monument translated Christian salvation history into an inner-worldly communist interpretation of the concentration camp as a place of political martyrdom and political rebirth: a new, better, socialist Germany had grown out of struggle and sacrificial death.

The National Memorial of the GDR

A "Lagerarbeitsgemeinschaft" ("camp working group") comprised of former inmates approved by the SED controlled the historical image. Memorial visits became an official part of education in the GDR. Collective rallies, "Jugendweihen" (youth dedications), swearing-in ceremonies of young pioneers and the FDJ (Free German Youth) or the National People's Army, class and company outings, training courses and sporting events were all moved to Buchenwald. Anti-Fascism was one of the fundamental principles in the official moral structure of the GDR. The less the future seemed to belong to socialism, the more important the substitute value tradition of an Anti-Fascist past became.

The last section of the exhibition traces precisely this form of regimented memory and shows how it gradually lost its desired community-building power.

Leitmotifs of the Buchenwald Memory

The various narratives on Buchenwald in the GDR essentially followed five leitmotifs: